“Language of the Birds” – 12th Century

Language of the Birds (Persian: منطق الطیر, Manṭiq-uṭ-Ṭayr, also known as مقامات الطیور Maqāmāt-uṭ-Ṭuyūr; 1177), is a mystical twelfth century Persian literary masterpiece by poet Farid ud-Din Attarin, commonly known as Attar of Nishapur. The poem title, which is in Arabic, is taken directly from the Qur’an, 27:16, where Sulayman (Solomon) and Dāwūd (David) are said to have been taught the language, or speech, of the birds (manṭiq al-ṭayr).

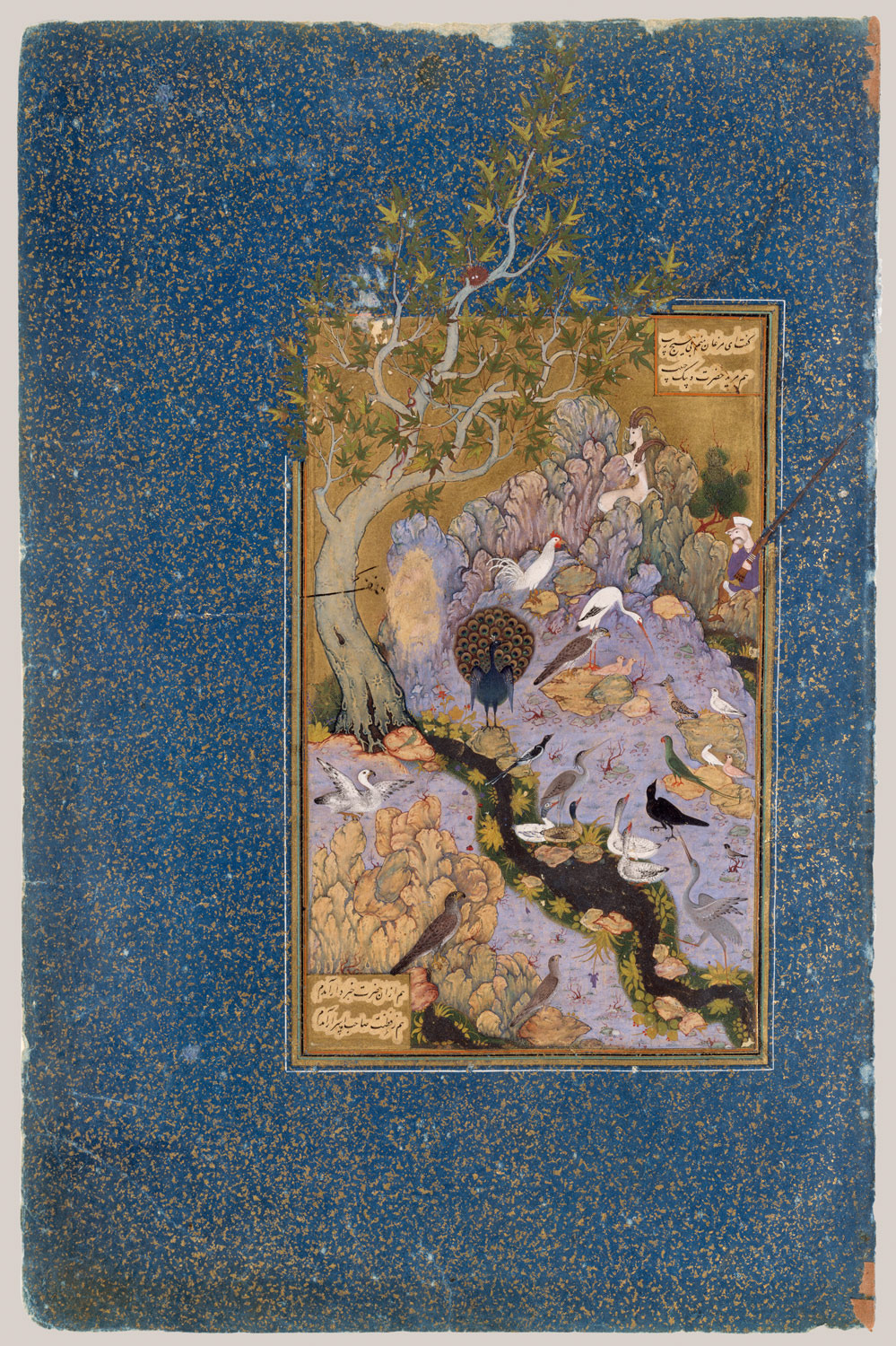

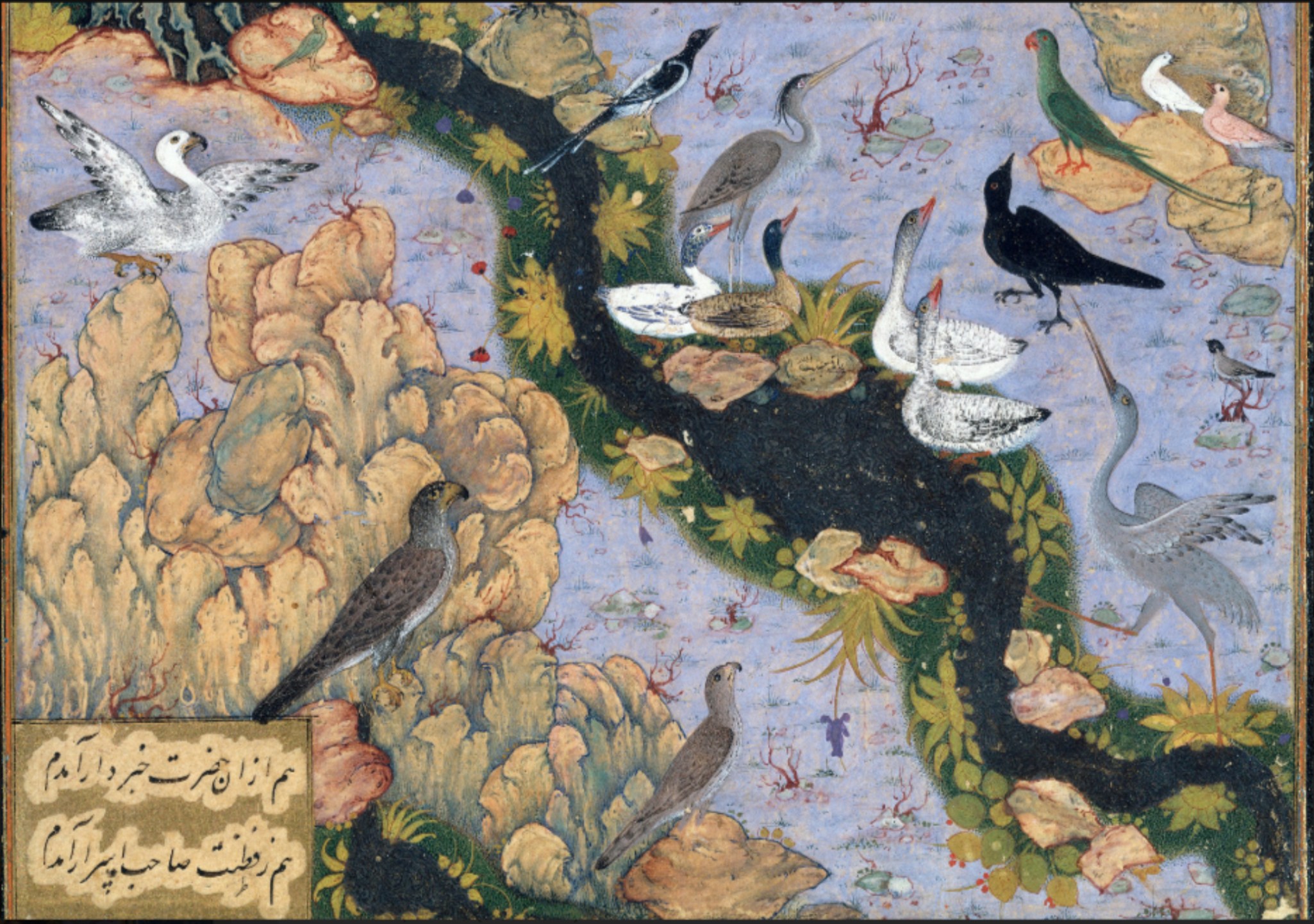

The birds, searching for a leader in the poem, are used as a symbol for mankind in search of God. The painting depicts assembled birds in idyllic landscape that are about to start the search for ‘Simurg’, the mystical bird, known as ‘Phoenix’ in Western cultures.

This Art Work – 16th Century

The work is produced on paper using ink, gold, silver and watercolour.

” This miniature, painted about 1600 by Habib Allah, has an almost magical quality in keeping with the nature of the theme.” (quote Swietochowski, M.,et.al. p.1)

“The illustration on this folio depicts a scene from a mystical poem, Mantiq al-tair (Language of the Birds), written by a twelfth-century Iranian, Farid al-Din ‘Attar. The birds, which symbolize individual souls in search of the simurgh (a mystical bird representing ultimate spiritual unity), are assembled in an idyllic landscape to begin their pilgrimage under the leadership of a hoopoe (perched on a rock at center right). MetMuseum

More About the Poem

Yumiko Kamada explains further:

“Attar (ca. 1142–1220), the author of the Mantiq al-tair, is one of the most celebrated poets of Sufi literature and inspired the work of many later mystical poets. The story is as follows: The birds assemble to select a king so that they can live more harmoniously. Among them, the hoopoe, who was the ambassador sent by Sulaiman to the Queen of Sheba, considers the Simurgh, or a Persian mythical bird, which lives behind Mount Qaf, to be the most worthy of this title.

When the other birds make excuses to avoid making a decision, the hoopoe answers each bird satisfactorily by telling anecdotes, and when they complain about the severity and harshness of the journey to Mount Qaf, the hoopoe tries to persuade them. Finally, the hoopoe succeeds in convincing the birds to undertake the journey to meet the Simurgh. The birds strive to traverse seven valleys: quest, love, gnosis, contentment, unity, wonder, and poverty.

Finally, only thirty birds reach the abode of the Simurgh, and there each one sees his/her reflection in the celestial bird. Thus, thirty birds see the Simurgh as none other than themselves. In this way, they finally achieve self-annihilation. This story is an allegorical work illustrating the quest of Sufism; the birds are a metaphor for men who pursue the Sufi path of God, the hoopoe for the pir (Sufi master), the Simurgh for the Divine, and the birds’ journey the Sufi path.” quote Heilbrunn Timeline

The Quest

According to Priscilla P. Soucek,

“Farid al-din ‘Attar’s epic poem the Mantiq al-tair (Language of the Birds), composed about 1187, is a parable about the desire for union with God that is couched in the terminology of sufism. It describes a physical and spiritual journey through seven valleys by a group of birds that move from their initial quest (talab) to their final goal of annihilation of the self (fana) through unity with God. The stages of their journey are explained through the use of anecdotes.” [Ekhtiar, Soucek, Canby, and Haidar 2011] Quote from MetMuseum

The Seven Valleys

The hoopoe leads the birds, each of whom represents a human fault which prevents human kind from attaining enlightenment. The hoopoe tells the birds that they have to cross seven valleys in order to reach the abode of Simorgh.

These valleys are as follows:.

1. Valley of the Quest, where the Wayfarer begins by casting aside all dogma, belief, and unbelief.

2. Valley of Love, where reason is abandoned for the sake of love.

3. Valley of Knowledge, where worldly knowledge becomes utterly useless.

4. Valley of Detachment, where all desires and attachments to the world are given up. Here, what is assumed to be “reality” vanishes.

5. Valley of Unity, where the Wayfarer realizes that everything is connected and that the Beloved is beyond everything, including harmony, multiplicity, and eternity.

6. Valley of Wonderment, where, entranced by the beauty of the Beloved, the Wayfarer becomes perplexed and, steeped in awe, finds that he or she has never known or understood anything.

7. Valley of Poverty and Annihilation, where the self disappears into the universe and the Wayfarer becomes timeless, existing in both the past and the future.

The Peacock’s Feet – Who Knew?

Then like a Sultan glittering in all Rays Of Jewelry, and deckt with his own Blaze, 290 The glorious Peacock swept into the Ring: And, turning slowly that the glorious Thing Might fill all Eyes with wonder, thus said He. 'Behold, the Secret Artist, making me, With no one Colour of the skies bedeckt, But from its Angel's Feathers did select To make up mine withal, the Gabriel Of all the Birds: though from my Place I fell In Eden, when Acquaintance I did make In those blest days with that Sev'n-headed Snake, 300 And thence with him, my perfect Beauty marr'd With these ill Feet, was thrust out and debarr'd. Little I care for Worldly Fruit or Flower, Would you restore me to lost Eden's Bower, But first my Beauty making all complete With reparation of these ugly Feet.' 'Were it,' 'twas answer'd, 'only to return To that lost Eden, better far to burn In Self-abasement up thy pluméd Pride, And ev'n with lamer feet to creep inside—310 But all mistaken you and all like you That long for that lost Eden as the true; Fair as it was, still nothing but the shade And Out-court of the Majesty that made. That which I point you tow'rd, and which the King I tell you of broods over with his Wing, With no deciduous leaf, but with the Rose Of Spiritual Beauty, smells and glows: No plot of Earthly Pleasance, but the whole True Garden of the Universal Soul.' 320

Quoted from Internet Archive Bird parliament by Attar, translated by Edward FitzGerald, 1889

Click For Enlarged Detail

Slideshow best viewed At Sunnyside

Is This a Hoopoe?

“The crested bird at the far right, with a dove immediately behind it, is a hoopoe, which is known in Iran as the tajidar, or “crown wearer.” The crest and “mystic mark” on its breast supposedly signified its special relationship with divinity. In Islamic tradition the hoopoe is known as King Solomon’s messenger. In this poem it leads the other birds in their pilgrimage. The long-tailed bird below the hoopoe is apparently an Indian parakeet. Next to the peacock is a goshawk and, just above it, a stork.”

quote Swietochowski, M.,et.al. p.2) from MetMuseum

Click for Enlarged View

More About the Painting

According to Sheila Canby quoted at TheMet,

“This painting illustrates a point in ‘Attar’s mystical manuscript when the birds assemble to discuss their journey in search of a king. Here the hoopoe standing on a rock at the right addresses the other birds as one initiated into the ‘way of spirital knowledge’, and urges the birds to seek the Simurgh, their true king.[1] At the upper right a man holding a musket with a large barrel gazes at the scene from behind the rocks. The composition, with the different species of birds silhouetted on a blue ground, jutting rocks above and at the lower left, a towering plane tree extending into the margin, and a gold sky, is extremely rich in detail and color harmonies”. quoted [Canby 2009]

Three Clues

“The careful, harmonious composition is consistent with that of the late fifteenth-century Timurid miniatures also in the manuscript, but three factors indicate that this image is later: the presence of the hunter, who has no place in the narrative; his firearm, a weapon that gained currency in Iran after the mid-sixteenth century; and the signature of the late sixteenth- to early seventeenth-century artist Habiballah.”

Quote from MetMuseum

“Both the musket, which is of a type made only from the late sixteenth century, and the signature of the artist, Habib Allah, on a rock between the duck and the geese confirm that this is one of the Safavid additions to the manuscript.”[2] quoted [Canby 2009]

Click for Enlarged View

Are They Pictures of Real Birds?

Spoiler Alert

Finally, only thirty birds make it to the abode of Simorgh. In the end, the birds learn that they themselves are the Simorgh; the name “Simorgh” in Persian means thirty (si) birds (morgh). They eventually come to understand that the majesty of that Beloved is like the sun that can be seen reflected in a mirror. Yet, whoever looks into that mirror will also behold his or her own image.”[3]

- If Simorgh unveils its face to you, you will find

- that all the birds, be they thirty or forty or more,

- are but the shadows cast by that unveiling.

- What shadow is ever separated from its maker?

- Do you see?

- The shadow and its maker are one and the same,

- so get over surfaces and delve into mysteries.[4]

Sholeh Wolpé, in the foreword of her modern translation of this work writes:

“The parables in this book trigger memories deep within us all. The stories inhabit the imagination, and slowly over time, their wisdom trickles down into the heart. The process of absorption is unique to every individual, as is each person’s journey. We are the birds in the story. All of us have our own ideas and ideals, our own fears and anxieties, as we hold on to our own version of the truth. Like the birds of this story, we may take flight together, but the journey itself will be different for each of us. Attar tells us that truth is not static, and that we each tread a path according to our own capacity. It evolves as we evolve. Those who are trapped within their own dogma, clinging to hardened beliefs or faith, are deprived of the journey toward the unfathomable Divine, which Attar calls the Great Ocean.” .[5]

Modern Interpretation

Provenance

Shah Abbas I, Isfahan, Iran (ca. 1600–1609; presented to Ardebil Shrine); Ardebil Shrine, Iran (ca. 1609–sack of Ardebil, 1826); M. Farid Parbanta(until 1963; sale, Sotheby’s, London,December 9, 1963, no. 111, to MMA)

For More Information

Essays

Timelines

Books I Want

- The Conference of the Birds, translated by Sholeh Wolpé W.W. Norton & Co 2017

- The Canticle of the Birds: Illustrated Through Persian and Eastern Islamic Art Slp Editionby

Thanks for Visiting 🙂

~Sunnyside

Just Beautiful. One can stare at it for hours

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am glad you like it, too. Thanks for visiting! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

So Adorable 😊

LikeLike

Hi Sunny – thanks for visiting! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure! Sunnyside…🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

so much more than meets the eyes

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, you are right. When I started it was just a lovely piece of art that caught my eye, but learning a little about the historical and cultural context made it so much more special. Thanks for visiting, roos. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely beautiful. Thank you for the extra information, so interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am happy you enjoyed it, Yvonne. Thanks so much for sharing your thoughts. 🙂

LikeLike

An amazing work of art with its own mystical story to tell.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The story got away with me a bit, but I was fascinated by the narrative as much as the art and history. 🙂 Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Rosaliene.

LikeLiked by 1 person